Osteoarthritis of the Knee

Anatomy

The knee is the biggest and most important joint in the human body. It is a hinge type joint connecting the lower thigh bone (femoral condyles) with the upper shin bone (tibial plateau). The hinged nature of the knee joint allows both bending (flexion) and straightening (extension). There is also a small amount of rotation that occurs in the knee when it is in a slightly bent position. The knee joint is critical for walking, sitting, squatting, and kneeling. It is a very stable joint due to the surrounding ligaments. The kneecap (patella) lies in front of the knee joint and forms part of the knee joint proper.

The knee joint can be divided into three compartments:

- Patellofemoral

- Medial compartment

- Lateral compartment.

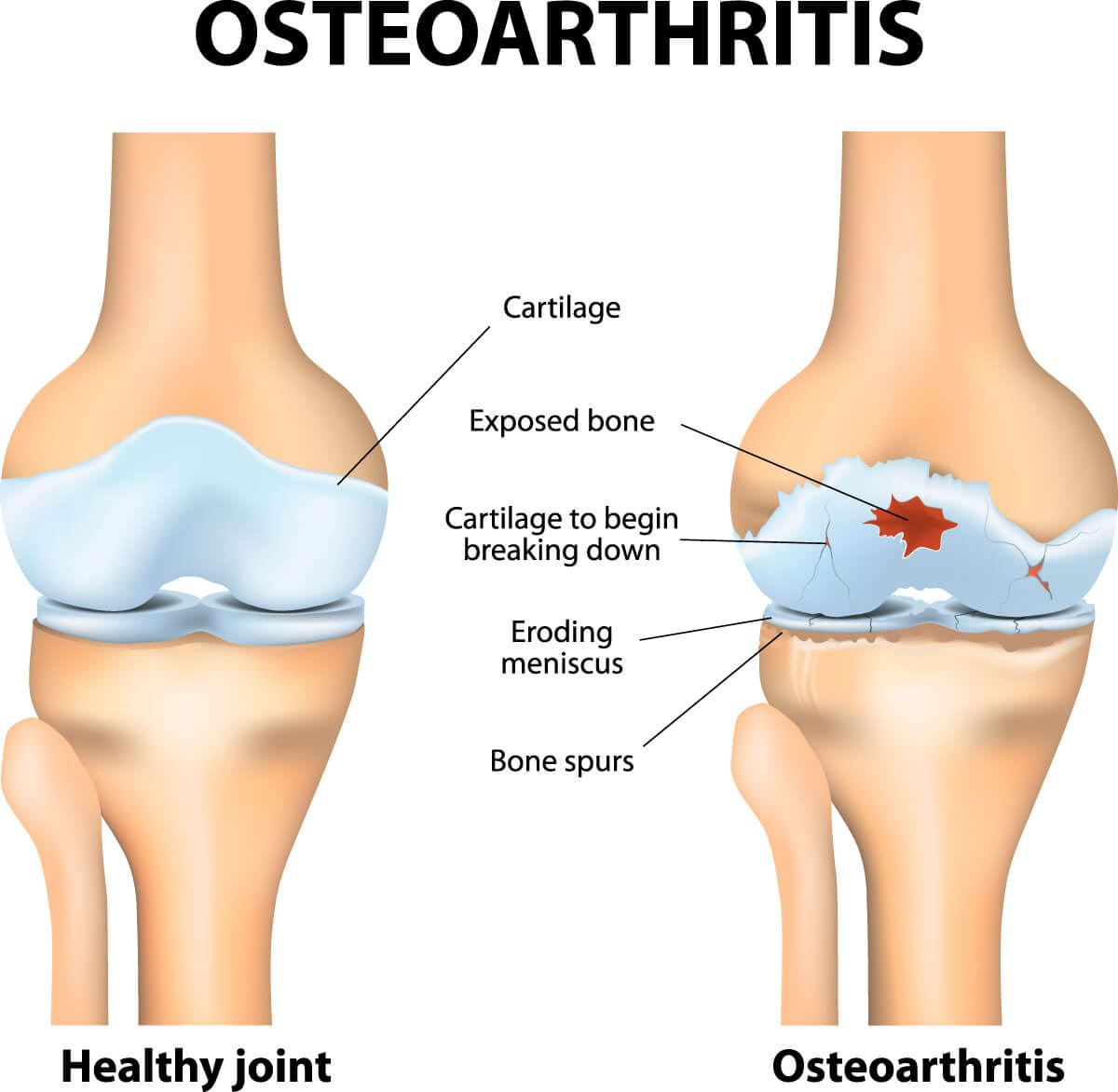

The surfaces of the bones are covered by a thin layer of a gristle type substance called hyaline articular cartilage. Lying between the femur and tibia is a horseshoe shape substance made of strong tough fibro cartilage and this is called the meniscus. There is one on the inside and one on the outside of the knee. The meniscus acts as the shock absorber to the smooth surfaces particularly during more vigorous running activities.

Normal knee anatomy

The joint is surrounded by a thin layer of synovium from which a small amount of oily fluid is produced to help lubricate the knee and reduce friction.

Osteoarthritis of the knee joint is a common condition in adults. It is more common in older patients but can affect younger patients as well. This type of arthritis involves a wearing away of the articular cartilage. The underlying bone becomes rough and irregular, and the synovium of the joint becomes thickened and inflamed, producing excessive fluid. Osteoarthritis usually develops slowly and in most cases the pain gradually increases with time. Although there is no cure for osteoarthritis of the knee, there are many ways in which a patient can manage the symptoms. Approximately one in six patients over the age of forty-five will experience symptoms related to osteoarthritis.

Symptoms

Although the pain usually comes on gradually during middle age over a number of months or years, it may sometimes start very suddenly and may be associated with severe pain and swelling.

- Knee pain is the most predominant symptom of osteoarthritis. It is usually worse in the morning and with increased activity as the knee condition progresses it can be present most of the time and can wake patients at night.

- The knee can become swollen both due the presence of excess fluid as well as bony enlargement.

- The knee can lock or catch due to rough and irregular surfaces. It can be compared with driving on a dirt road with many corrugations. The knee may feel weak and may sometimes collapse or give way.

- It is often difficult to squat and kneel.

- Getting out of a chair or out of a car to start walking often causes momentary increase in pain.

Causes of osteoarthritis

- Increasing age – osteoarthritis is more common in middle age and older patients, and is degenerative in nature.

- Genetic – there are some families who have a strong history of knee osteoarthritis. In some cases, it can be due to a generalised primary osteoarthritis and those patients often have the condition in both knees as well as an acquired deformity of the hands.

- Previous trauma – a prior history of a meniscal tear or anterior cruciate ligament tear predisposes the knee to developing osteoarthritis. There is no evidence that performing an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction reduces the risk of developing osteoarthritis compared with patients who receive conservative treatment for that condition. A prior history of fracture to the femur, tibia or patella will also increase the risk of subsequent osteoarthritis.

- Obesity – this is one of the major causes of knee osteoarthritis. Patients who are obese have four to six times the risk of developing symptoms from this condition when compared with patients with normal weight.

Imaging

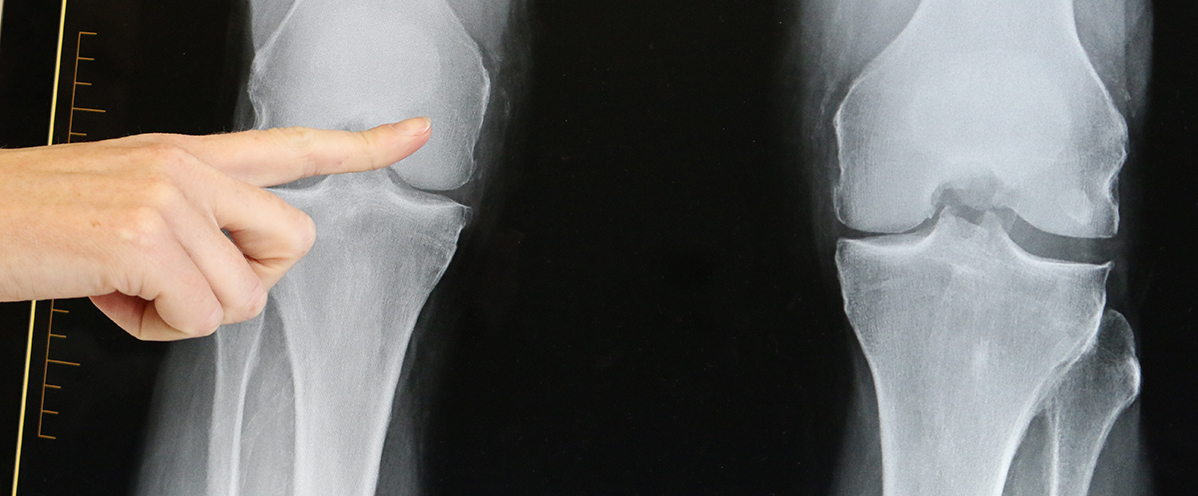

In most cases weight bearing x-rays of the knee are sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of osteoarthritis. Occasionally an MRI may be helpful where the degenerative changes are milder and where the symptoms are more in keeping with damage to the meniscus. When the x-rays confirm marked osteoarthritis an MRI will not be helpful in managing the condition.

(Left) In this x-ray of a normal knee, the space between the bones indicates healthy cartilage (arrows). (Right) This x-ray of an arthritic knee shows severe loss of joint space.

Management

Conservative treatment

Although there is no cure for knee osteoarthritis, there are a number of management strategies that can be beneficial in reducing the symptoms.

Lifestyle modifications

It is best to minimise activities that aggravate this knee condition, such as avoiding high impact activities, running and repetitive stair climbing. It is however important to maintain a level of activity. Aerobic exercise that does not aggravate the joint will produce endorphins, which act as your own natural painkiller as well as giving a sense of general wellbeing. Joining a gym and performing gentle activities such as low impact aerobic classes, using a stationary bicycle or ergo machine can be helpful.

Weight reduction

This is probably the most important but challenging management strategy for patients suffering from knee osteoarthritis. In our Western culture, obesity is rapidly on the rise and has a number of causes. In part, it is due to our sedentary lifestyle but it is also due to the type of food we eat rather than the amount. Simple calorie restriction is rarely successful nor are fad diets.

There is now growing scientific evidence that a diet based on protein, fat and vegetables can be very successful in achieving weight reduction and maintaining that weight loss. This goes against all the previous mainstream medical advice which emphasised low fat diets. In our supermarkets we are surrounded by highly processed most of which are high in carbohydrates. The foods labelled low fat are often loaded with sugar to make them palatable. Our bodies can do without these carbohydrates. Switching over to a low carbohydrate diet, many patients notice a diminished hunger due to a reduction in the hunger hormones produced by carbohydrates. Below there are two websites that have further information on this form of food management.

This website comes from Professor Tim Noakes, a leading South African sports physician. This is an extremely useful website in how to lose weight and provides excellent science behind why we should not fear eating saturated fats.

This website is produced by Dr Gary Fettke, an orthopaedic surgeon in Tasmania, who has thoroughly investigated the causes of obesity. He was prompted to undertake this investigation after seeing increasing numbers of patients with knee osteoarthritis in early middle age.

Strengthening exercises

There are several scientific publications demonstrating the significant benefit from strengthening the thigh muscles (quadriceps) in reducing pain and feelings of instability in the knee. Beneficial activities include bicycle riding, swimming, yoga, and Tai chi. Referral to a physiotherapist or an exercise physiologist may be helpful in guiding you in appropriate exercises.

Assistive devices

Using a walking stick for longer walks may well be helpful in diminishing pain and feelings of insecurity as well as enabling patients to walk longer distances. Unloading knee braces can also be very beneficial in significantly relieving symptoms in some patients. There is no evidence that wearing orthotics in shoes will make any difference to the symptoms of knee arthritis.

Medication

Many patients are reluctant to consider taking medications because of the fear of causing long-term health problems but are willing to consider invasive surgery. In most cases invasive surgery carries a much greater risk than the potential side effects from these medications.

- Panadol or Panadol Osteo – these are very safe drugs and for many patients will obtain excellent pain relief if taken regularly. Like all medications some patients will respond better to some than others.

- Anti-inflammatory agents – these are often called NSAID’s such as Nurofen, Naproxen or Voltaren. These can be used in conjunction with Panadol, and assist with pain relief by reducing the inflammatory component of the arthritic joint condition.

- Steroid injections into the knee – this can sometimes be helpful in the acute flare-ups when the knee swells significantly and may be used in conjunction with a knee arthroscopy. The effects of steroid injections are only temporary and should be avoided three to six months prior to knee joint replacement surgery because of increased risk of infection.

- Visco supplementation – the knee can be injected with substances such as Synvisc. Some initial studies showed that it was beneficial for up to six months following injection with mild to moderate arthritis, but more recent studies have shown minimal benefit over the placebo.

- Glucosamine and chondroitin sulphate – these substances are found normally in joint articular cartilage and can be taken as a dietary supplement. You will note that they take up several aisles of the discount chemist stores! Some patients find this medication to be helpful in relieving their symptoms. Randomised controlled trials have shown only limited benefit over placebo. If they are not producing a significant improvement in symptoms within 2 months patients should seriously consider ceasing this medication. There is no evidence that they decrease or reverse the progression of arthritis.

Surgical treatment

There are a number of surgical procedures that may be beneficial but, as with all surgeries, there are some risks and potential complications with different knee procedures. This will be discussed at the time of your consultation.

Arthroscopy

Up until recently, knee arthroscopy with wash out of the damaged articular cartilage has been used commonly. There are now several randomised studies showing no benefit over sham surgery or placebo or conservative treatment. Occasionally there can be benefit when the degenerative changes are mild and there are symptoms due to a torn meniscus or loose body.

Arthroscopic micro fracture

If there is localised damage to the articular cartilage, some patients will benefit from drilling small holes into the underlying bone to promote healing of the defect.

Articular cartilage grafting

This requires two operations several weeks apart. In the first operation which is done arthroscopically, a small amount of the patient’s normal articular cartilage is taken and then cartilage cells are grown onto a patch outside the body for several weeks. A second procedure involves inserting the cartilage patch onto the articular cartilage defect. There has been some controversy as to its benefits and the graft is no longer rebatable in private hospitals in Australia.

Osteotomy

In this procedure the upper tibia or femur is cut and the lower limb repositioned in order to take the pressure away from the localised diseased area within the knee joint. It is particularly helpful for patients who are younger and active. It can delay knee replacement surgery for many years and can allow the patient to return to an active sporting lifestyle. It does however take some months to recover from such surgery.

Total knee replacement

This is an excellent option when conservative measures have failed and the symptoms are disabling. A knee replacement can be either total or partial.

For the majority of patients, a total knee replacement would be indicated. In approximately one in four patients a partial knee replacement can be performed where the disease is confined to one part of the joint only, and the joint is not significantly out of alignment or stiff.